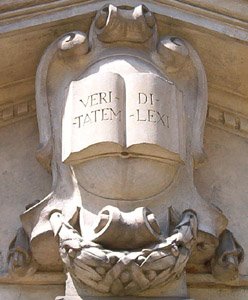

A Christian Sarcophagus

In honor of Good Friday/Easter, I thought I'd post a couple of photographs of a Christian sarcophagus currently on display in the Vatican Museums.

Regarding the type of symbolic centerpiece used in this sarcophagus, Andre Grabar writes the following:

'This first type of image of the Resurrection [i.e. the type he has been discussing in the foregoing paragraphs, not the type shown in the photographs here], which I call juridical and evangelical (because, like the Gospels, it evoked dogma by showing the story of the eyewitnesses of the Resurrection), was not the only one that the image-makers invented. It outweighed all the others, however, from about 400 until the eleventh century in the West and until modern times in the Byzantine world. But in the fourth century, probably in Rome, another image was invented, symbolic in its iconography, that had great success but was abandoned a hundred or a hundred and twenty years later, perhaps because its meaning had become obscure. It was a figuration inspired by the art of military triumphs of pagan Roman tradition, and as it became further removed from pagan times, it must have appeared less explicit. It is on Roman sarcophagi of the fourth century that we find almost all the examples. Here we see the military trophy, and in it the phoenix--symbol of the Resurrection--with seated or standing figures on either side. The origins of this iconography are recognizable in the reliefs of a pagan sarcophagus where the usual military trophy, displaying the arms of the vanquished, is represented, along with the barbarians beneath it who were conquered by the Romans. The Christian formula replaces the trophy by the Cross, on which is suspended a triumphal crown, and substitutes for the captured barbarians two armed but sleeping soldiers--in an allusion to the guardians of the tombe of Christ: their arms are as powerless to prevent the victorious Resurrection of Christ as the arms of the barbarians were powerless before those of the Imperial armies.'

--from Christian Iconography: A Study of its Origins (Princeton 1968), pp. 124-5